Manufacturing Account

Difference in Accounting for Stocks between Manufacturing Companies and Merchandising Companies

Explain the difference in accounting for stocks between manufacturing companies and merchandising companies

The businesses which produce and sell the items prepare the following accounts at the end of its accounting year:-

- The Manufacturing account (to calculate the total cost of production)

- The Trading and profit & loss account (to find out the net profit or loss)

- The balance sheet.(to show the financial position of the business)

The total cost of production = Prime cost + Factory overhead

The Prime cost = Direct material + Direct labour + Direct expenses

Direct

material cost = Opening stock of raw materials + purchase of raw

materials + carriage inwards – returns outwards – closing stock of raw

materials.

material cost = Opening stock of raw materials + purchase of raw

materials + carriage inwards – returns outwards – closing stock of raw

materials.

Factory overhead expenses = All expenses related to the factory (indirect expenses)

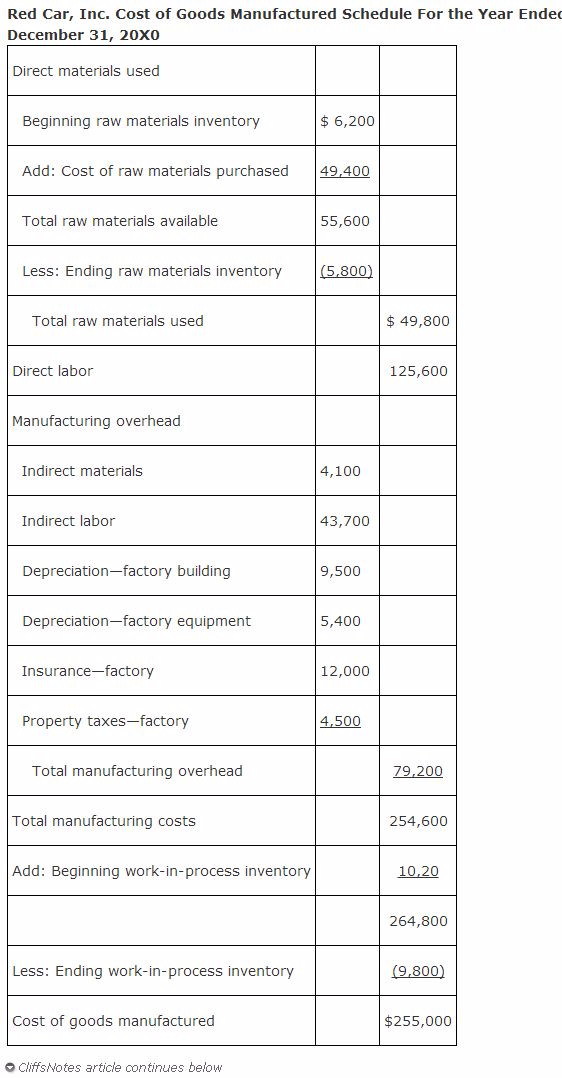

The format of a manufacturing account

Manufacturing account for the year ended . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

| Opening stock of raw materials | xxxx | |

| Add purchase of raw materials | xxxxx | |

| Add carriage inwards ( if any ) | Xxxx | |

| Xxxxx | ||

| Less Returns outwards (of raw materials) | xxxx | |

| Xxxxx | ||

| Less Goods drawings ( if any ) | xxxx | |

| xxxxx | ||

| Less Closing stock of raw materials | xxxx | |

| Cost of Direct Materials | xxxxxxx | |

| Add Direct labour | xxxxxxx | |

| Add Direct expenses (Eg: royalties) | xxxxxxx | |

| Prime Cost | xxxxxxx | |

| Add Factory overhead expenses | ||

| Factory lighting | xxxxxx | |

| Factory heating | xxxxxx | |

| Factory insurance | xxxxxx | |

| Factory rent | xxxxxx | |

| Factory maintenance | xxxxxx | |

| Factory indirect wages | xxxxxx | |

| Factory supervisor’s wages | xxxxxx | ( + ) |

| Depreciation on plant & machinery | xxxxxx | |

| Depreciation on factory building | xxxxxx | |

| Depreciation on factory furniture | xxxxxx | |

| Depreciation on factory motor van | xxxxxx | |

| Depreciation on other factory fixedassets | xxxxxx | XXXXXXX |

| XXXXXXX | ||

| Add Opening stock of work in progress | xxxxxx | |

| XXXXXXX | ||

| Less Closing stock of work in progress | xxxxxx | |

| Cost of production | XXXXXXX |

The Three Basic Types of Manufacturing Cost

Describe the three basic types of manufacturing cost

Manufacturing costs are the costs necessary to convert raw materials into products. Allmanufacturing costsmust

be attached to the units produced for external financial reporting

under USGAAP. The resulting unit costs are used forinventory valuationon

the balance sheet and for the calculation of thecost of goods soldon

the income statement.

be attached to the units produced for external financial reporting

under USGAAP. The resulting unit costs are used forinventory valuationon

the balance sheet and for the calculation of thecost of goods soldon

the income statement.

Manufacturing costs are typically divided into three categories:

- Direct materials.

This is the cost of the materials which become part of the finished

product. For example, the cost of wood is a direct material in the

manufacture of wooden furniture. - Direct labor.

This is the cost of the wages of the individuals who are physically

involved in converting raw materials into a finished product. For

example, the wages of the person cutting wood into the specified lengths

and the wages of the assemblers are direct labor costs in a furniture

factory. - Factory overhead ormanufacturing overhead.

Factory overhead refers to all other costs incurred in the

manufacturing activity which cannot be directly traced to physical units

in an economically feasible way. The wages of the person who inspects

the completed furniture and thedepreciationon the factory equipment are

part of the factory overhead costs. Factory overhead is also described

as indirect manufacturing costs.

Difference between Indirect and Direct Manufacturing Costs

Distinguish between indirect and direct manufacturing costs

When

you’re determining the price of a product, it’s obvious that you need

to charge more than the total cost of producing it. But production costs

go beyond the materials and equipment — you also need to factor in

workers’ salaries, marketing campaigns, overall company maintenance, and

the like. Taken all together, these expenses make up the direct and

indirect costs of running your business.

you’re determining the price of a product, it’s obvious that you need

to charge more than the total cost of producing it. But production costs

go beyond the materials and equipment — you also need to factor in

workers’ salaries, marketing campaigns, overall company maintenance, and

the like. Taken all together, these expenses make up the direct and

indirect costs of running your business.

It

is easy to classify the basic difference between direct and indirect

costs. Direct costs are immediately associated with the production of a

product or service, while indirect costs include such things as rent —

which may be associated with many products — or they may be several

steps back in the production process. Though it is tempting to ignore

the nuances of this accounting principle, spending some time correctly

allocating your costs can improve your accounting ledger — and your

clout with potential investors.

is easy to classify the basic difference between direct and indirect

costs. Direct costs are immediately associated with the production of a

product or service, while indirect costs include such things as rent —

which may be associated with many products — or they may be several

steps back in the production process. Though it is tempting to ignore

the nuances of this accounting principle, spending some time correctly

allocating your costs can improve your accounting ledger — and your

clout with potential investors.

Direct costs

Direct

costs are expenses that a company can easily connect to a specific

“cost object,” which may be a product, department or project. This

includes items such as software, equipment, labor and raw materials. If

your company develops software and needs specific pregenerated assets

such as purchased frameworks or development applications, those are

direct costs.

costs are expenses that a company can easily connect to a specific

“cost object,” which may be a product, department or project. This

includes items such as software, equipment, labor and raw materials. If

your company develops software and needs specific pregenerated assets

such as purchased frameworks or development applications, those are

direct costs.

Labor

and direct materials, which are used in creating a specific product,

constitute the majority of direct costs. For example, to create its

product, an appliance maker requires steel, electronic components and

other raw materials.

and direct materials, which are used in creating a specific product,

constitute the majority of direct costs. For example, to create its

product, an appliance maker requires steel, electronic components and

other raw materials.

Companies

typically track the cost of the finished raw materials as a direct

cost. Two popular ways of tracking these costsinclude last in, first out

(LIFO) or first in, first out (FIFO).

typically track the cost of the finished raw materials as a direct

cost. Two popular ways of tracking these costsinclude last in, first out

(LIFO) or first in, first out (FIFO).

While

salaries tend to be a fixed cost, direct costs are frequently variable.

Variable expenses increase as additional units of a product or service

are created, whereas an employee’s salary remains constant throughout

the year. For example, smartphone hardware is a direct, variable cost

because its production depends on the number of units ordered.

salaries tend to be a fixed cost, direct costs are frequently variable.

Variable expenses increase as additional units of a product or service

are created, whereas an employee’s salary remains constant throughout

the year. For example, smartphone hardware is a direct, variable cost

because its production depends on the number of units ordered.

Indirect costs

Indirect

costs go beyond the costs associated with creating a particular product

to include the price of maintaining the entire company. These overhead

costs are the ones left over after direct costs have been computed, and

are sometimes referred to as the “real” costs of doing business.

costs go beyond the costs associated with creating a particular product

to include the price of maintaining the entire company. These overhead

costs are the ones left over after direct costs have been computed, and

are sometimes referred to as the “real” costs of doing business.

The

materials and supplies needed for the company’s day-to-day operations

are examples of indirect costs. These include items such as cleaning

supplies, utilities, office equipment rental, desktop computers and cell

phones. While these items contribute to the company as a whole, they

are not assigned to the creation of any one service.

materials and supplies needed for the company’s day-to-day operations

are examples of indirect costs. These include items such as cleaning

supplies, utilities, office equipment rental, desktop computers and cell

phones. While these items contribute to the company as a whole, they

are not assigned to the creation of any one service.

Indirect

labor costs make the production of cost objects possible, but aren’t

assigned to a specific product. For example, clerical assistants who

help maintain the office support thecompany as a whole instead of just

one product line. Thus, their labor can becounted as an indirect cost.

labor costs make the production of cost objects possible, but aren’t

assigned to a specific product. For example, clerical assistants who

help maintain the office support thecompany as a whole instead of just

one product line. Thus, their labor can becounted as an indirect cost.

Other

common indirect costs include advertising and marketing, communication,

“fringe benefits” such as an employee gym, and accounting and payroll

services.

common indirect costs include advertising and marketing, communication,

“fringe benefits” such as an employee gym, and accounting and payroll

services.

Much

like direct costs, indirect costs can be both fixed and variable. Fixed

indirect costs include things like the rent paid for the building in

which a company operates. Variable costs include the ever-changing costs

of electricity and gas.

like direct costs, indirect costs can be both fixed and variable. Fixed

indirect costs include things like the rent paid for the building in

which a company operates. Variable costs include the ever-changing costs

of electricity and gas.

Difference between Product Costs and Period Costs

Distinguissh between product costs and period costs

The

key difference between product costs and period costs is that products

costs are only incurred if products are acquired or produced, and period

costs are associated with the passage of time. Thus, a business that

has no production or inventory purchasing activities will incur no

product costs, but will still incur period costs.

key difference between product costs and period costs is that products

costs are only incurred if products are acquired or produced, and period

costs are associated with the passage of time. Thus, a business that

has no production or inventory purchasing activities will incur no

product costs, but will still incur period costs.

Examples

of product costs are direct materials, direct labor, and allocated

factory overhead. Examples of period costs are general and

administrative expenses, such as rent, office depreciation, office

supplies, and utilities.

of product costs are direct materials, direct labor, and allocated

factory overhead. Examples of period costs are general and

administrative expenses, such as rent, office depreciation, office

supplies, and utilities.

Product

costs are sometimes broken out into the variable and fixed

subcategories. This additional information is needed when calculating

the break even sales level of a business. It is also useful for

determining the minimum price at which a product can be sold while still

generating a profit.

costs are sometimes broken out into the variable and fixed

subcategories. This additional information is needed when calculating

the break even sales level of a business. It is also useful for

determining the minimum price at which a product can be sold while still

generating a profit.

A Schedule of Cost of Finished Goods Manufactured

Prepare a schedule of cost of finished goods manufactured

Thecost

of goods manufactured scheduleis used to calculate the cost of

producing products for a period of time. The cost of goods manufactured

amount is transferred to the finished goods inventory account during the

period and is used in calculating cost of goods sold on the income

statement. The cost of goods manufactured schedule reports the total

manufacturing costs for the period that were added to work‐in‐process,

and adjusts these costs for the change in the work‐in‐process inventory

account to calculate the cost of goods manufactured.

of goods manufactured scheduleis used to calculate the cost of

producing products for a period of time. The cost of goods manufactured

amount is transferred to the finished goods inventory account during the

period and is used in calculating cost of goods sold on the income

statement. The cost of goods manufactured schedule reports the total

manufacturing costs for the period that were added to work‐in‐process,

and adjusts these costs for the change in the work‐in‐process inventory

account to calculate the cost of goods manufactured.

The

cost of goods manufactured for the period is added to the finished

goods inventory. To calculate the cost of goods sold, the change in

finished goods inventory is added to/subtracted from the cost of goods

manufactured

cost of goods manufactured for the period is added to the finished

goods inventory. To calculate the cost of goods sold, the change in

finished goods inventory is added to/subtracted from the cost of goods

manufactured

The Cost of Work in Process Stocks and the Costs of Finished Goods Stocks

Determine the cost of work in process stocks and the costs of finished goods stocks

Work

in process is goods in production that have not yet been completed.

These goods are situated between raw materials and finished goods in the

production process flow.

in process is goods in production that have not yet been completed.

These goods are situated between raw materials and finished goods in the

production process flow.

Inventory

in this classification typically involves the full amount of raw

materials needed for a product, since that is usually included in the

product at the beginning of the manufacturing process. During

production, the cost of direct labor and overhead is added in proportion

to the amount of work done. From the perspective of valuation, a WIP

item is more valuable than a raw materials item (since processing costs

have been added), but is not as valuable as a finished goods item (to

which the full set of processing costs have already been added).

in this classification typically involves the full amount of raw

materials needed for a product, since that is usually included in the

product at the beginning of the manufacturing process. During

production, the cost of direct labor and overhead is added in proportion

to the amount of work done. From the perspective of valuation, a WIP

item is more valuable than a raw materials item (since processing costs

have been added), but is not as valuable as a finished goods item (to

which the full set of processing costs have already been added).

In

prolonged production operations, there may be a considerable amount of

investment in work in process. Conversely, the production of some

products occupies such a brief period of time that the accounting staff

does not bother to track WIP at all; instead, the items in production

are considered to still be in the raw materials inventory. In this

latter case, inventory essentially shifts directly from the raw

materials inventory to the finished goods inventory, with no separate

work in process accounting at all.

prolonged production operations, there may be a considerable amount of

investment in work in process. Conversely, the production of some

products occupies such a brief period of time that the accounting staff

does not bother to track WIP at all; instead, the items in production

are considered to still be in the raw materials inventory. In this

latter case, inventory essentially shifts directly from the raw

materials inventory to the finished goods inventory, with no separate

work in process accounting at all.

Work

in progress accounting involves tracking the amount of WIP in inventory

at the end of an accounting period and assigning a cost to it for

inventory valuation purposes, based on the percentage of completion of

the WIP items.

in progress accounting involves tracking the amount of WIP in inventory

at the end of an accounting period and assigning a cost to it for

inventory valuation purposes, based on the percentage of completion of

the WIP items.

WIP

accounting can be incredibly complex for large projects that are in

process over many months. In those situations, we use job costing to

assign individual costs to projects. See thejob costingarticle for more

information.

accounting can be incredibly complex for large projects that are in

process over many months. In those situations, we use job costing to

assign individual costs to projects. See thejob costingarticle for more

information.

In

situations where there are many similar products in process, it is more

common to follow these steps to account for work in progress inventory:

situations where there are many similar products in process, it is more

common to follow these steps to account for work in progress inventory:

- Assign raw materials.

We assume that all raw materials have been assigned to work in process

as soon as the work begins. This is reasonable, since many types of

production involve kitting all of the materials needed to construct a

product and delivering them to the manufacturing area at one time. - Compile labor costs.

The production staff can track the time it works on each product, which

is then assigned to the work in process. However, this is painfully

time-consuming, so a better approach is to determine the stage of

completion of each item in production, and assign a standard labor cost

to it based on the stage of completion. This information comes from

labor routings that detail the standard amount of labor needed at each

stage of the production process. - Assign overhead. If

overhead is assigned based on labor hours, then it is assigned based on

the labor information compiled in the preceding step. If overhead is

assigned based on some other allocation methodology, then the basis of

allocation (such as machine hours used) must first be compiled. - Record the entry.

This journal entry involves shifting raw materials from the raw

materials inventory account to the work in process inventory account,

shifting direct labor expense into the work in process inventory

account, and shifting factory overhead from the overhead cost pool to

the WIP inventory account.

It

is much easier to usestandard costsfor work in process accounting.

Actual costs are difficult to trace to individual units of production,

unless job costing is being used. However, standard costs are not as

precise as actual costs, especially if the standard costs turn out to be

inaccurate, or there are significant production inefficiencies beyond

what were anticipated in the standard costs.

is much easier to usestandard costsfor work in process accounting.

Actual costs are difficult to trace to individual units of production,

unless job costing is being used. However, standard costs are not as

precise as actual costs, especially if the standard costs turn out to be

inaccurate, or there are significant production inefficiencies beyond

what were anticipated in the standard costs.

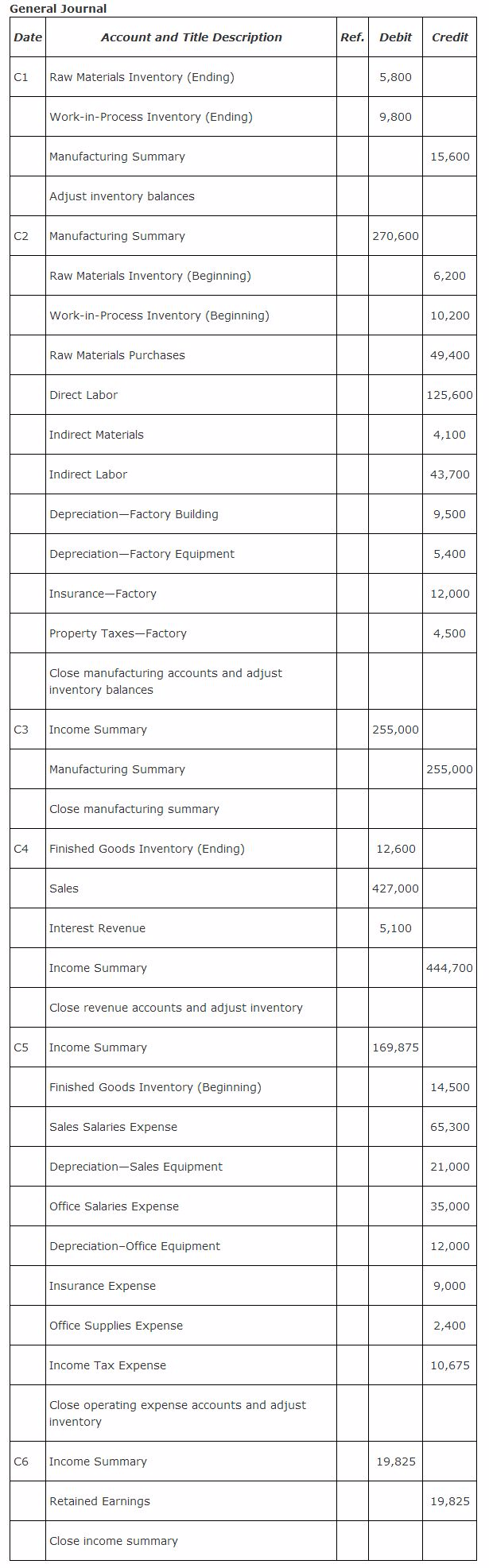

Closing Entries for a Manufacturing Company

Prepare closing entries for a manufacturing company

Some

companies use one account, factory overhead, to record all costs

classified as factory overhead. If one overhead account is used, factory

overhead would be debited in the previous entry instead of factory

depreciation.

companies use one account, factory overhead, to record all costs

classified as factory overhead. If one overhead account is used, factory

overhead would be debited in the previous entry instead of factory

depreciation.

At

the end of the cycle, the closing entries are prepared. For a

manufacturing company that uses the periodic inventory method, closing

entries update retained earnings for net income or loss and adjust each

inventory account to its period end balance. A special account called

manufacturing summary is used to close all the accounts whose amounts

are used to calculate cost of goods manufactured. The manufacturing

summary account is closed to income summary. Income summary is

eventually closed to retained earnings. The manufacturing accounts are

closed first. The closing entries that follow are based on the accounts

included in the cost of goods manufactured schedule and income statement

for Red Car, Inc.

the end of the cycle, the closing entries are prepared. For a

manufacturing company that uses the periodic inventory method, closing

entries update retained earnings for net income or loss and adjust each

inventory account to its period end balance. A special account called

manufacturing summary is used to close all the accounts whose amounts

are used to calculate cost of goods manufactured. The manufacturing

summary account is closed to income summary. Income summary is

eventually closed to retained earnings. The manufacturing accounts are

closed first. The closing entries that follow are based on the accounts

included in the cost of goods manufactured schedule and income statement

for Red Car, Inc.

The following T‐accounts illustrate the impact of the closing entries on the special closing accounts and retained earnings.

The Basic Differences in the Financial Statements of Manufacturing Companies and Merchandising Companies

Describe the basic differences in the financial statements of manufacturing companies and merchandising companies

The

most significant difference between a manufacturing company and a

merchandising business is that a manufacturer makes goods to sell and a

merchandiser buys or acquires goods for resale. In developing a small

business, it is critical to understand whether your strengths, available

resources and environmental factors contribute to a manufacturing or

merchandising setup.

most significant difference between a manufacturing company and a

merchandising business is that a manufacturer makes goods to sell and a

merchandiser buys or acquires goods for resale. In developing a small

business, it is critical to understand whether your strengths, available

resources and environmental factors contribute to a manufacturing or

merchandising setup.

- Expertise:

Given their primary functions of either making or acquiring goods for

resale, expertise is a core difference between manufacturing and

merchandising. A successful manufacturing business features expertise in

developing an operation that produces high-quality, efficient or

high-value goods and then distributing them. A merchandiser owns

strengths in acquiring goods, increasing their value and marketing them

to buyers. A distributor buys items and then resells to retailers,

consumers or business buyers. A retailer buys goods and then resells to

consumers. - Relationship: Manufacturers and

merchandisers also have different roles in their interrelationship

within a traditional distribution channel. The distribution or trade

channel represents the flow of goods from manufacturer through

distribution, retailer and on to the final customer. The manufacturer

makes goods and traditionally sells them to the distributor or retailer.

Wholesaling merchandisers are the traditional direct buyer of

manufacturers, although retailers may buy directly from manufacturers as

well. - Marketing Strategies: Manufacturers

typically use a combination of “push” and “pull” marketing strategies.

Pull marketing occurs when the manufacturer promotes its brands to end

customers. The idea it to create market demand and pull the products

through the distribution process. Push marketing occurs when a

manufacturer promotes goods directly to trade buyers, or merchandisers.

This includes a mix of communicating benefits and offering trade

incentives or discounts. Retailer merchandising businesses focus on

promoting their company and product brands to targeted customers. They

must attract customers to make sales. - Inventory:

For manufacturers, production inventory includes raw materials used in

producing finished goods. Low costs and efficient use of raw inventory

is key in manufacturing profitability. Once raw materials are converted,

the manufacturer possesses a finished-goods inventory. A reseller buys

finished goods and either holds its new inventory in a distribution

center or in storage areas in stores. When floor inventory or

merchandise grows low, stock is replenished by retail associates.

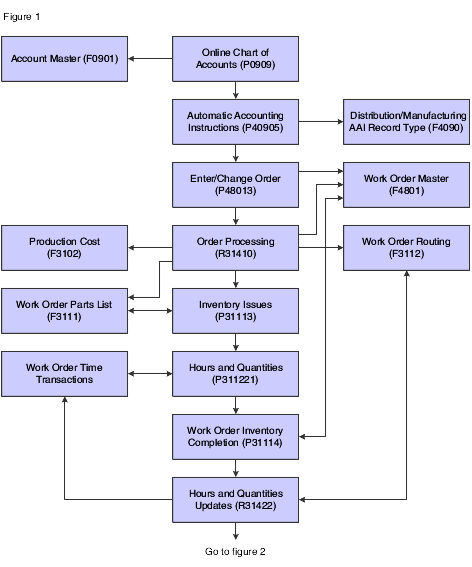

The procedure Inherent in a General Accounting System for a Manufacturing Company

Describe the procedure inherent in a general accounting system for a manufacturing company

Understanding the JD Edwards EnterpriseOne Manufacturing Accounting System

This two-part flowchart illustrates the manufacturing accounting processes:

Manufacturing Accounting process flow

Integration with General Accounting

To

remain competitive in a changing business environment, companies must

integrate all aspects of their operations. This integration includes

identifying operations that reduce lead times, expedite speed-to-market,

and reduce operating costs. The objective is to reduce costs to remain a

competitive market player.

remain competitive in a changing business environment, companies must

integrate all aspects of their operations. This integration includes

identifying operations that reduce lead times, expedite speed-to-market,

and reduce operating costs. The objective is to reduce costs to remain a

competitive market player.

After

a company defines item costs and identifies how each cost is derived,

it transfers these cost records into the accounting records. Using a

manufacturing accounting system enables you to track the costs that are

associated with each activity within the manufacturing process. As

material is received into inventory, issued to a manufacturing order,

and used at various stages of the manufacturing cycle, the company

maintains detailed accounting records that reflect debits and credits to

predetermined financial accounts. These records can be transferred to

the general ledger throughout the manufacturing cycle.

a company defines item costs and identifies how each cost is derived,

it transfers these cost records into the accounting records. Using a

manufacturing accounting system enables you to track the costs that are

associated with each activity within the manufacturing process. As

material is received into inventory, issued to a manufacturing order,

and used at various stages of the manufacturing cycle, the company

maintains detailed accounting records that reflect debits and credits to

predetermined financial accounts. These records can be transferred to

the general ledger throughout the manufacturing cycle.

The

ability to perform standard costing (comparisons based on frozen costs)

or actual costing (comparison of expected cost versus actual cost)

enables companies to accurately account for the cost of manufacturing.

Comparisons identify specific costs that deviate from the original cost

expectations. This information enables managers to make better informed

decisions and to implement a course of action that reflects current

costs in the ultimate cost of the products. Work in process and on-hand

inventory can be revalued to reflect these updated costs.

ability to perform standard costing (comparisons based on frozen costs)

or actual costing (comparison of expected cost versus actual cost)

enables companies to accurately account for the cost of manufacturing.

Comparisons identify specific costs that deviate from the original cost

expectations. This information enables managers to make better informed

decisions and to implement a course of action that reflects current

costs in the ultimate cost of the products. Work in process and on-hand

inventory can be revalued to reflect these updated costs.

In

volatile and dynamic industries such as electronics and other

technologies, changes in technology and customer demand, product

configuration, and production processes must be monitored constantly.

Changes must be integrated and reflected throughout product life cycles

as quickly as possible. Industries remain competitive in the global

marketplace only if they minimize the time to market for new products

and reduce costs.

volatile and dynamic industries such as electronics and other

technologies, changes in technology and customer demand, product

configuration, and production processes must be monitored constantly.

Changes must be integrated and reflected throughout product life cycles

as quickly as possible. Industries remain competitive in the global

marketplace only if they minimize the time to market for new products

and reduce costs.

This

flowchart illustrates the interaction between the JD Edwards

EnterpriseOne Manufacturing Accounting system and the JD Edwards

EnterpriseOne General Accounting system:

flowchart illustrates the interaction between the JD Edwards

EnterpriseOne Manufacturing Accounting system and the JD Edwards

EnterpriseOne General Accounting system:

Integration between Manufacturing Accounting and General Accounting systems

Different Accounts that Appear on a Manufacturing Company’s Books

List the different accounts that appear on a manufacturing company’s books

The balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s:

- assets(what it owns)

- liabilities(what it owes)

- owners’ equity(net worth – what’s left over for the owners)

The

balance sheet shapshot is at a particular point in time, such as at the

close of business on December 31. The simplest corporate balance sheet

possible, showing only totals and leaving out all detail, might look

like this.

balance sheet shapshot is at a particular point in time, such as at the

close of business on December 31. The simplest corporate balance sheet

possible, showing only totals and leaving out all detail, might look

like this.

| ALBEGA CORPORATIONBalance SheetDecember 31, 20xx | |||

| Assets | $485,000 | Liabilities | $ 285,000 |

| Shareholders’ Equity | $200,000 | ||

| Total Assets | $485,000 | Total Liabilities and Shareholders’ Equity | $485,000 |

Balance sheet equation.Assets

are always equal to the liabilities plus equity. You can see the

balance sheet as a statement of what the company owns (assets) and the

persons having claims to the assets (creditors and owners). Here is the

balance sheet equation:

are always equal to the liabilities plus equity. You can see the

balance sheet as a statement of what the company owns (assets) and the

persons having claims to the assets (creditors and owners). Here is the

balance sheet equation:

| Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity | |

| Assets | Liabililities |

| Shareholders’ Equity | |

The

equation reflects how information is organized on the balance sheet,

with assets listed on the left and liabilities and equity on the right.

Like the equation, the two sides of the balance sheet must balance.

equation reflects how information is organized on the balance sheet,

with assets listed on the left and liabilities and equity on the right.

Like the equation, the two sides of the balance sheet must balance.

Double entry bookkeeping.The

balance sheet equation also reflects the way information is recorded in

the company records. Too keep the equation in balance, company

transactions are recorded using “double entry bookkeeping.” Every

transaction will cause two changes on the accounting statements — that

is, a transaction that affects one side of the equation will also affect

the other side, unless there are two offsetting entries on one side.

For example, a $2,000 increase in assets will also result in either:

balance sheet equation also reflects the way information is recorded in

the company records. Too keep the equation in balance, company

transactions are recorded using “double entry bookkeeping.” Every

transaction will cause two changes on the accounting statements — that

is, a transaction that affects one side of the equation will also affect

the other side, unless there are two offsetting entries on one side.

For example, a $2,000 increase in assets will also result in either:

- an offsetting decrease in assets (if the new $2,000 asset was purchased with $2,000 cash)

- an increase in liabilities (if the company borrowed the $2,000 to buy the asset)

- an increase in equity (if the $2,000 came from contributions by the company’s owners).

Reading balance sheet.Let’s read a more detailed version of our balance sheet:

| ALBEGA CORPORATIONBalance SheetDecember 31, 20xx | |||

| ASSETS | LIABILITIES | ||

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities | ||

| Cash | $ 50,000 | Accounts Payable | $ 60,000 |

| Accounts receivable (net of allowance for bad debts of $5,000) | $175,000 | Notes payable (including current portion of long-term debt) | $ 40,000 |

| Inventory (FIFO) | $125,000 | Income taxes payable | $ 25,000 |

| Total current assets | $350,000 | Total current liabilities | $125,000 |

| Non-current Assets | Long Term Liabilities | ||

| Plant | $ 50,000 | 5-year notes payable | $160,000 |

| Property | $ 75,000 | Total Liabilities | $285,000 |

| Equipment | $ 50,000 | ||

| Fixed assets | $175,000 | SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY | |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | ($ 50,000) | Common stock ($1.00 par value; 1,000 shs authorized, issued + outstanding) | $ 1,000 |

| Net fixed assets | $125,000 | Paid-in capital in excess of par value | $ 49,000 |

| Intangibles (patents) | $ 10,000 | Retained earnings | $150,000 |

| Total non-current assets | $ 135,000 | Total Shareholders’ Equity | $200,000 |

| Total Assets | $485,000 | Total Liabilities and Shs’ Equity | $485,000 |

What the Accounts in a Manufacturing Company’s Books Represent

State what the accounts in a manufacturing company’s books represent

Assets

The

assets accounts show how the company has used the money it has obtained

from lenders, investors, and company earnings. Technically, according

to GAAP, assets are resources with “probable future economic benefits

obtained or controlled by an entity resulting from pasttransactionsor

events.” This leads to some non-intuitive results. Importantresources

like intellectual property or longstanding business relationships,

though valuable to a business, are generally not reflected on the

balance sheet.

assets accounts show how the company has used the money it has obtained

from lenders, investors, and company earnings. Technically, according

to GAAP, assets are resources with “probable future economic benefits

obtained or controlled by an entity resulting from pasttransactionsor

events.” This leads to some non-intuitive results. Importantresources

like intellectual property or longstanding business relationships,

though valuable to a business, are generally not reflected on the

balance sheet.

Assets

are grouped as monetary (cash and accounts receivables), liquid

(whether they can easily be converted to cash), tangible or intangible.

are grouped as monetary (cash and accounts receivables), liquid

(whether they can easily be converted to cash), tangible or intangible.

In our example the asset categories are:

- Current assets:cash and those items, such as accounts receivable, that are normally expected to be converted into cash within one year.

- Non-current assets:Fixed

assets: the company’s more or less permanent physical assets, such as

its land, buildings, machinery and equipment; Intangible assets:

goodwill, trademarks, copyrights, patents (reader beware!)

Current Assets

Cash.

– This includes not only currency, which a company might keep in “petty

cash,” but also bank deposits, U.S. Treasury notes, money market

accounts, and other “cash equivalents.” If the company had to pay a

ransom, how much could it pay today?

– This includes not only currency, which a company might keep in “petty

cash,” but also bank deposits, U.S. Treasury notes, money market

accounts, and other “cash equivalents.” If the company had to pay a

ransom, how much could it pay today?

Accounts Receivable.

– If a company sells goods or services on credit, the amounts owed to

the company by customers are “accounts receivable.” The company must,

however, anticipate that some of the accounts receivable will not be

received. An account, such as “allowance for bad debts,” is set-off

(subtracted) from the accounts receivable shown in the balance sheet.

The allowance, often based on a percentage, is usually based on the

company’s past collection experience. This presents a fairer picture of

how much the company will likely receive from its sales on credit.

– If a company sells goods or services on credit, the amounts owed to

the company by customers are “accounts receivable.” The company must,

however, anticipate that some of the accounts receivable will not be

received. An account, such as “allowance for bad debts,” is set-off

(subtracted) from the accounts receivable shown in the balance sheet.

The allowance, often based on a percentage, is usually based on the

company’s past collection experience. This presents a fairer picture of

how much the company will likely receive from its sales on credit.

Inventory.

– For a manufacturing company, inventory includes goods used in the

business at various stages of production: raw materials, work in process

and finished goods. Other companies have other types of inventory. For

example, a retail store has in inventory only the purchased goods it

sells. Service companies have no inventory. The generally accepted

method of inventory valuation is to record the inventory at its cost or

market value, whichever is lower (here “market value” is not retail

value, but what it would cost the company to replace the inventory).

– For a manufacturing company, inventory includes goods used in the

business at various stages of production: raw materials, work in process

and finished goods. Other companies have other types of inventory. For

example, a retail store has in inventory only the purchased goods it

sells. Service companies have no inventory. The generally accepted

method of inventory valuation is to record the inventory at its cost or

market value, whichever is lower (here “market value” is not retail

value, but what it would cost the company to replace the inventory).

Inventory

Things

get trickier for the cost of goods in various stages of the

manufacturing process. Two common ways to measure the “cost” of

inventory purchased at different times and at varying prices are:

get trickier for the cost of goods in various stages of the

manufacturing process. Two common ways to measure the “cost” of

inventory purchased at different times and at varying prices are:

- First-in, first-out (“FIFO “).

Under the FIFO method of valuation, inventory items purchased first are

deemed to be sold first. Under this method, the most recent purchase

prices are deemed to represent the cost of the items remaining. For

example, suppose that the purchases and sales of a particular item are

as follows:Under FIFO, the cost of the ending inventory (300 items)

would be $250 ($.90 each for 100 and $.80 each for 200). When prices are

rising, FIFO results in inventory being shown on the balance sheet at

the highest possible amount.

| Quantity | Cost per item | Total Cost | |

| Jan. Purchase | 100 | $ .60 | $ 60 |

| Mar. Purchase | 500 | .70 | $350 |

| June Purchase | 300 | .80 | $240 |

| Sep. Purchase | 100 | .90 | $ 90 |

| Total purchases | 1,000 | $740 | |

| Less sales | 700 | ||

| Ending inventory | 300 | ?? | ?? |

- Last-in, first-out (“LIFO “).

Under LIFO, the items of inventory purchased last are deemed to be sold

first — so the cost of the ending inventory is deemed the cost of the

items purchased first. In our example, the cost of the ending inventory

(300 items) would be $200 ($.60 for each 100 items and $.70 each for 200

items)

Non-current Assets – Fixed Assets

Fixed

assets — such as land, buildings, machinery and equipment — are

typically shown on the balance sheet at their cost, less accumulated

depreciation.

assets — such as land, buildings, machinery and equipment — are

typically shown on the balance sheet at their cost, less accumulated

depreciation.

Historical cost.How are assets valued for purposes of the balance sheet? There are several possibilities:

- historical cost (how much the company paid to acquire it)

- current market value

- value in use

- liquidation value based on its sale after use.

Assets are typically recorded on financial statements at theirhistorical costexpressed in dollars.

Depreciation.

What is depreciation / depletion / amortization? these are all terms

that refer to alloocating the cost of along-lived asset to consecutive

accounting periods as expenses until the full cost is fully accounted

for.

What is depreciation / depletion / amortization? these are all terms

that refer to alloocating the cost of along-lived asset to consecutive

accounting periods as expenses until the full cost is fully accounted

for.

- “Depreciation”

describes the allocation of the cost of certain fixed assets over their

estimated useful lives. (Land is not depreciated, since its useful life

for accounting purposes is unlimited.) - “Depletion” describes the case of “wasting assets,” such as oil and gas fields.

- “Amortization”

is used for intangible assets, such as patents or trademarks.

Amortization of R&D expenses is controversial. Under GAAP such

expenses are expensed currently, even though they may have long-term

payoffs.

When

a fixed asset is depreciated, the cost of the asset is allocated over

its expected useful life, and each annual installment of depreciation is

added to an account called “accumulated depreciation. ” On the balance

sheet, accumulated depreciation is set-off against the total fixed

assets (shown at their total cost at time of purchase).

a fixed asset is depreciated, the cost of the asset is allocated over

its expected useful life, and each annual installment of depreciation is

added to an account called “accumulated depreciation. ” On the balance

sheet, accumulated depreciation is set-off against the total fixed

assets (shown at their total cost at time of purchase).

Notice that the balance sheet does not reflect appreciation in the value of assets, such as when there is inflation.

How is depreciation calculated? There are two common methods:

- Straight-line method.–

The straight line depreciation method, the most common, calculates

depreciation by dividing the cost of the asset, less its salvage value,

by its estimated useful life. - Double declining balance method. – The double declining balance method calculates depreciation by takingtwicethe

straight-line depreciation percentage rate and multiplying this

percentage rate by the initial cost of the asset (in the first year) or

by each declining balance amount (in succeeding years). The asset is not

depreciated below a reasonable salvage value.

The double declining balance method is a kind ofaccelerated depreciationsince

it produces more depreciation in the initial years of an asset’s life

than does the straight-line method. For tax

purposesaccelerateddepreciationhas the advantage ofreducing taxable

income during early years of asset;s life — and as we know, tax savings

now are worth more than tax savings later.

it produces more depreciation in the initial years of an asset’s life

than does the straight-line method. For tax

purposesaccelerateddepreciationhas the advantage ofreducing taxable

income during early years of asset;s life — and as we know, tax savings

now are worth more than tax savings later.

Example 1

A

wine press purchased for $50,000 has an estimated useful life of 5

years and a salvage value of $10,000. What is its annual depreciation

using a straight-line method? a double-declining balance method?

wine press purchased for $50,000 has an estimated useful life of 5

years and a salvage value of $10,000. What is its annual depreciation

using a straight-line method? a double-declining balance method?

| Year | Depreciation | Depreciation |

| Straight-line | Double-declining | |

| 1 | (50,000 – 10,000) / 5 = $ 8,000 | 50,000 x 40% = $ 20,000 |

| 2 | (50,000 – 10,000) / 5 = $ 8,000 | (50,000-20,000) x 40% = $12,000 |

| 3 | (50,000 – 10,000) / 5 = $ 8,000 | (30,000-12,000) x 40% = $7,200 |

| 4 | (50,000 – 10,000) / 5 = $ 8,000 | $ 800 |

| 5 | (50,000 – 10,000) / 5 = $ 8,000 | $0 |

| Annual % | 20% | varies |

The annual depreciation using a straight-line method is $8,000 — that is, 20% per year,

The

annual depreciation using a double-declining method varies. After three

years, the cumulative depreciation is $39,200. Assuming a salvage value

of $10,000, the last depreciation amount of $800 comes in the fourth

year when the salvage figure is reached.

annual depreciation using a double-declining method varies. After three

years, the cumulative depreciation is $39,200. Assuming a salvage value

of $10,000, the last depreciation amount of $800 comes in the fourth

year when the salvage figure is reached.

Intangible Assets

This

item has become more important as intellectual property (patents,

trademarks, copyrights) has become the darlings of the information age.

Typically, IP is carried at its acquisition or development cost.

item has become more important as intellectual property (patents,

trademarks, copyrights) has become the darlings of the information age.

Typically, IP is carried at its acquisition or development cost.

Vapor.

But intangible assets, particularly goodwill, raise tricky issues. Are

these unseen, untouchable assets just vapor? On the one hand, it is easy

to overstate their value, particularly since there usually is no ready

market to compare. On the other hand, intangible assets may represent an

importan part of the company’s overall business value. (For example,

some business valuatiors hav calculated that the Coca-Cola trademark —

forget the secret formula — is worth a real $80 billion.) exists

But intangible assets, particularly goodwill, raise tricky issues. Are

these unseen, untouchable assets just vapor? On the one hand, it is easy

to overstate their value, particularly since there usually is no ready

market to compare. On the other hand, intangible assets may represent an

importan part of the company’s overall business value. (For example,

some business valuatiors hav calculated that the Coca-Cola trademark —

forget the secret formula — is worth a real $80 billion.) exists

Goodwill.

What about goodwill — that is, the value the business derives from

brand names, reputation, management quality, customer loyalty or

recognized location? Typically, goodwill is not accounted for.

Classified as an intangible asset, goodwill is recorded on a company’s

books only when it is acquired in a business acquisition. Sometimes,

goodwill is valued as the difference between the price paid for a

company as a going concern and the fair market value of its assets minus

liabilities.

What about goodwill — that is, the value the business derives from

brand names, reputation, management quality, customer loyalty or

recognized location? Typically, goodwill is not accounted for.

Classified as an intangible asset, goodwill is recorded on a company’s

books only when it is acquired in a business acquisition. Sometimes,

goodwill is valued as the difference between the price paid for a

company as a going concern and the fair market value of its assets minus

liabilities.

Liabilities

The

second portion of the balance sheet consists of the company’s

liabilities — usually separated into current liabilities and long-term

liabilities. Liabilities can be understood as the opposite of assets —

they represent obligations of the business. Not all obligations to make a

payment in the future are reflected on the balance sheet. For example,

an obligation to pay employees’ rising health care costs may be a

signficant commitment , it might not be represented on the balance sheet

if sufficiently uncertain. Or the prospect of paying clean-up fees for a

toxic site owned by the business may not make it to the balance sheet,

though it may be described in a note.

second portion of the balance sheet consists of the company’s

liabilities — usually separated into current liabilities and long-term

liabilities. Liabilities can be understood as the opposite of assets —

they represent obligations of the business. Not all obligations to make a

payment in the future are reflected on the balance sheet. For example,

an obligation to pay employees’ rising health care costs may be a

signficant commitment , it might not be represented on the balance sheet

if sufficiently uncertain. Or the prospect of paying clean-up fees for a

toxic site owned by the business may not make it to the balance sheet,

though it may be described in a note.

- Current

liabilities: those debts that are to be paid within 12 months. These

include accounts payable, short-term notes payable and income taxes

payable. Also included are accrued expenses payable, such as for

employees wages and salaries, insurance premiums, attorney fees, and

taxes due. - Long-term liabilities: any debt that is not due

within one year, such as long-term debts and notes. In the case of a

debt that is partially due within one year and partially due in future

years, the portion of the debt payable within one year is shown as a

current liability and the rest as a long-term liability.

One

important potential drain on a business are contingent liabilities,

such as possible products liability claims or securities fraud exposure.

These are not carried on the balance sheet.

important potential drain on a business are contingent liabilities,

such as possible products liability claims or securities fraud exposure.

These are not carried on the balance sheet.

Owners’ Equity

The

third and final portion of a balance sheet represents the owners’

equity. In a sole proprietorship (a business with one owner), the

ownership account is known as “proprietor’s equity”; in a partnership,

the ownership account is “partners’ capital.”

third and final portion of a balance sheet represents the owners’

equity. In a sole proprietorship (a business with one owner), the

ownership account is known as “proprietor’s equity”; in a partnership,

the ownership account is “partners’ capital.”

In

a corporation, the ownership accounts are divided into three

categories, reflecting accounting conventions found in state corporation

statutes. Accountants, however, use their own nomenclature for these

accounts [the corporation statutory term in in brackets]

a corporation, the ownership accounts are divided into three

categories, reflecting accounting conventions found in state corporation

statutes. Accountants, however, use their own nomenclature for these

accounts [the corporation statutory term in in brackets]

- Common stock [stated capital].

This is calculated by multiplying the number of shares of stock

outstanding by the par value of each share. In our balance sheet above,

the par value of the corporation’s common stock is $1.00 per share and

1,000 shares have been issued, yielding a stated capital of $1,000. (Par

value is an arbitrary dollar figure assigned to stock to determine

stated capital; some corporation statutes — particularly Delaware’s —

restrict a corporation’s distributions based on stated capital.) - Paid-in capital in excess of par [capital surplus].

This is the difference between what shareholders paid the corporation

for their stock and the stock’s par value. In our example, the

corporation sold 1,000 shares of common stock for $50 each — $1,000

shown in common stock and $49,000 shown in paid-in capital in excess of

par value. (Some corporation statutes also restrict distributions based

on capital surplus). - Retained earnings [earned surplus].

This shows the total profits and losses of the corporation since its

formation, decreased by any dividends paid the shareholders. If the

corporation has had losses rather than profits, retained earnings is

negative (indicated by placing the number in parenthesis). That is, as

the business makes or loses money, this is the item that gets adjust (up

or down) to balance the “balance sheet.”

One

way to see equity is aspermanentnon-debt capitalization of the business

— that is, captal assets and accumulated profitsless

anydistributionsto the owners. Each year the equity account changes with

the ebb and flow of revenuesand expenses — creating a link between

theincome statementand balance sheet.

way to see equity is aspermanentnon-debt capitalization of the business

— that is, captal assets and accumulated profitsless

anydistributionsto the owners. Each year the equity account changes with

the ebb and flow of revenuesand expenses — creating a link between

theincome statementand balance sheet.

The Purpose of Manufacturing Account

Explain the purpose of a manufacturing Account

The

purpose of a Manufacturing Account is to ascertain Cost of Production (

).Cost of Production = Prime Cost + Factory Overheads + Opening Work in

Progress – Closing Work in Progress

purpose of a Manufacturing Account is to ascertain Cost of Production (

).Cost of Production = Prime Cost + Factory Overheads + Opening Work in

Progress – Closing Work in Progress

How a Manufacturing Account is Composed

Explain how a manufacturing Accounts is composed

A

manufacturing account shows the cost of producing the goods that are

sold during an accounting period. It is split into the following

sections:

manufacturing account shows the cost of producing the goods that are

sold during an accounting period. It is split into the following

sections:

- Prime cost– Direct costs of physically making the products (e.g. raw materials)

- Overhead cost– Other indirect costs associated with production but not in a direct manner

The

cost of manufacturing the products will be the total of the prime cost

and the overhead cost added together. This total factory cost (or

production cost) will then be transferred to the trading account where

it will appear instead of the ‘normal’ purchases figure.

cost of manufacturing the products will be the total of the prime cost

and the overhead cost added together. This total factory cost (or

production cost) will then be transferred to the trading account where

it will appear instead of the ‘normal’ purchases figure.

Prime cost

The

prime cost covers all the costs involved in physically making the

products and other costs that are directly related to the level of

output. These are usually known as direct costs and common examples

would include:

prime cost covers all the costs involved in physically making the

products and other costs that are directly related to the level of

output. These are usually known as direct costs and common examples

would include:

- Direct materials

- Direct labour/wages

- Other direct costs (e.g. packaging, royalties)

Cost of raw materials consumed

Within

the prime cost adjustments will have to be made for opening and closing

stocks of raw materials. There may also be carriage inwards charged on

the raw materials and returns outwards of materials sent back to their

original supplier. The overall charge for materials is referred to as

cost of raw materials consumed, this should be highlighted when drawing

up a manufacturing account and it is calculated as follows:

the prime cost adjustments will have to be made for opening and closing

stocks of raw materials. There may also be carriage inwards charged on

the raw materials and returns outwards of materials sent back to their

original supplier. The overall charge for materials is referred to as

cost of raw materials consumed, this should be highlighted when drawing

up a manufacturing account and it is calculated as follows:

| – | Opening stock of raw materials |

| – | Purchases of raw materials |

| Add | |

| Carriage inwards on raw materials | Less |

| Returns outwards of raw materials | |

| Less | Closing stock of raw materials |

| Equals | Cost of raw materials consumed |

A

true direct cost will vary directly with the level of output. If the

output level doubles, then we would expect a direct cost to also double.

If the cost does not behave in this manner then it may be an indirect

cost and not a direct cost.

true direct cost will vary directly with the level of output. If the

output level doubles, then we would expect a direct cost to also double.

If the cost does not behave in this manner then it may be an indirect

cost and not a direct cost.

Royalties

Royalties

is sometimes included within the prime cost. These are a cost that is

paid to the owner of a copyrighted process. Usually a fee is paid for

each product that uses this process and therefore the total royalty cost

will be directly proportional to the level of output.

is sometimes included within the prime cost. These are a cost that is

paid to the owner of a copyrighted process. Usually a fee is paid for

each product that uses this process and therefore the total royalty cost

will be directly proportional to the level of output.

Overhead cost

This

section includes all other expenses concerned with the production of

output but not in a direct manner.This means that if the level of

production increased, then these expenses may also increase but not by

the same proportion. These are sometimes known as indirect costs,

factory overheads or indirect manufacturing costs. Common examples of

overhead costs would include:

section includes all other expenses concerned with the production of

output but not in a direct manner.This means that if the level of

production increased, then these expenses may also increase but not by

the same proportion. These are sometimes known as indirect costs,

factory overheads or indirect manufacturing costs. Common examples of

overhead costs would include:

- Factory rent

- Indirect labour

- Depreciation of factory plant and equipment

Depreciation

of fixed assets should be included in this section only if it is

depreciation on assets included for production. For example,

depreciation of machinery would appear as an overhead cost but

depreciation of office equipment would appear in the profit and loss

account as an expense as would be expected in a non-manufacturing

organisation.

of fixed assets should be included in this section only if it is

depreciation on assets included for production. For example,

depreciation of machinery would appear as an overhead cost but

depreciation of office equipment would appear in the profit and loss

account as an expense as would be expected in a non-manufacturing

organisation.

Once

the overhead costs have been calculated they will need adding to the

total of the prime cost. This will give us the production cost of the

goods. However, the production cost will need adjusting for goods which

are not yet finished.

the overhead costs have been calculated they will need adding to the

total of the prime cost. This will give us the production cost of the

goods. However, the production cost will need adjusting for goods which

are not yet finished.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog post. Keep writing.

Thanks a lot for the blog post.Much thanks again. Want more.

Thank you ever so for you blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

Major thanks for the blog.Thanks Again. Cool.

Really informative blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article.Much thanks again. Want more.